Gullion added to Board of Directors

At the May, 2024 meeting of the NCFHS we welcomed Beulah Gullion of Belews Creek, NC, to our Board of Directors. Beulah has an impressive educational background receiving an Associates in Arts from Surry Community College in 2020 and a Bachelors in History and Quaker Studies from Guilford College in 2022. At Guilford Beulah did a work study at the Quaker Archives, was an ECAR volunteer, and a QLSP Scholar. This past year Beulah began the Master of Divinity Program at Earlham School of Religion and is presently transferring to finish her MDiv in 2026 at Wake Forest University’s School of Divinity. IN 2022 Beulah was the recipient of North Carolina Friends Historical Society’s Poole Writing Award. Beulah’s paper was entitled “Friends Divided: Willie Frye and the Conflict of Consciences”. (See the FELLOWSHIPS page on this website).

Beulah is presently part-time faculty at New Garden Friends School where she

teaches World History. In Beulah’s free time she enjoys reading lots of sci-fi, poetry, and her most favorite of all…. personal memoirs. From 2017 to 2021 Beulah worked at Quaker Lake Camp, first as summer staff and then as year round staff. Beulah’s love for the outdoors continues to inform her passion for outdoor education and spending time in nature, especially hiking in the Blue Ridge and long days at the beach. Beulah loves her dog Benson, the Cincinnati Reds, sewing, and crocheting.

The present board of directors looks forward to gaining fresh insight from Beulah as we discern the best ways to appeal to the younger lovers of Quaker History? How do we reach that audience? We have our eyes set on the future, and our future lies with the generations to come.

2023 Poole Writing Award is lead article in Fall 2023 Quaker History

The 2023 Poole Writing Award recipient Holly C. Schulman’s award winning essay, “Dolley Madison, Quaker by Birth and Slave Owner by Choice,” is the lead article in the just out Fall 2023 issue of Quaker History. The editors note prefacing the article highlights the article as the 2023 Poole Award winner and quotes the NCFHS Fellowship Committee’s positive assessment of the work.

Also, reminder that applications are now being accepted for the 2024 Hinshaw Fellowship. The Seth and Mary Edith Hinshaw Fellowship provides up to $2,000 for research using the resources of the Quaker Archives at Guilford College to study an aspect of southern Quaker history. Application deadline is March 1. See https://library.guilford.edu/archives/fellowships for more information.

Ruth Anne Hood (July 28, 1930 – January 3, 2024)

Ruth Anne Schoonmaker Hood, 93, passed away peacefully after a brief illness while surrounded by children, their spouses, and grandchildren, at Wesley Long Hospital, Wednesday, January 3, 2024.

Ruth Anne was born in South Amherst, Massachusetts, the seventh child of Robert Selleck Schoonmaker and Esther Head Cadbury Schoonmaker, growing up on a farm where her family raised chickens and apples. She attended local schools, graduating from Amherst High School in 1947. She continued her education at Oberlin College, receiving her degree in Religion with a minor in Sociology. While at Oberlin, she met and fell in love with Malcolm Woodhams Hood, of Kenmore, New York, whom she married on August 24, 1951 following their graduation that year. Together they raised a family of five children, moving around the country for various educational and job-related reasons before settling in Miami Springs, Florida, in 1962.

In addition to being a full-time homemaker and caregiver for her husband due to his severe rheumatoid arthritis, Ruth Anne worked in Christian education at Miami Springs United Methodist Church and as a teacher’s assistant, first at Miami Springs Elementary School and later at Guilford Primary School in Greensboro, following her husband’s abrupt death in 1982 and her subsequent move to North Carolina in 1983. After retiring from Guilford County Public Schools, she volunteered for twenty-four years at the Friends Historical Collection (now the Quaker Archives) at Guilford College and for the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC) as a regional representative. She was a long-time, active member of New Garden Friends Meeting, serving the meeting in multiple capacities.

She moved to Friends Homes in Greensboro in 2009, where she greatly enjoyed cherished friendships, working in the Library, and serving on the House and Grounds Committee.

Her Quaker family heritage and a work trip to Lima, Ohio, sponsored by the AFSC in the summer of 1949, inspired her lifelong interest in peace and social justice work. She spoke out publicly in favor of school desegregation in Miami in the early 1970s when opposition to busing white children to black schools was vitriolic, and she participated in protests against the Vietnam and Iraq wars, at times taking her children and grandchildren along. She served on the New Garden Friends Meeting Peace and Social Concerns Committee, sustaining her concern for those traditionally excluded from the rights and privileges due to all.

While she enjoyed gardening, knitting, music, reading, watching old movies, and travel-including memorable trips to England, New Zealand, Alaska, her cherished New England, and the American west-family always stayed at the center of her attention. She felt particularly blessed to have had a reunion this past fall with many nieces, nephews, children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren from all around the country. She was especially devoted to her five children, their spouses, and their families.

She was preceded in death by her parents; her loving husband, Malcolm; all her six siblings and their spouses; two nephews; and her grandson, Jonathan Mooneyham. She is survived by her children-Kate Seel (Roger), Jim (Sara Beth Terrell), Stephen (Mary), David (Pam), and Alan (Erica Martin)-seven grandchildren-Julia, Rachel Mooneyham, Daniel (Madeleine Straubel), James (Mary Elise Topp), Andrew, Morgan Kollmeyer (Peter), and Kathryn-and her great-grandchildren-Caroline Ruth Wilson, Pamela Louise Kollmeyer, and Maya Toporowsky-Hood.

A service in the manner of Friends celebrating Ruth Anne’s life will take place in the Living Room at Friends Homes on Sunday, January 7, 2024 at 3 p.m.

In lieu of flowers, please send contributions to the American Friends Service Committee, 1501 Cherry Street, Philadelphia, PA 19102 (AFSC.org) or the charity of your choice.

Forbis & Dick Guilford Chapel

5926 W. Friendly Avenue

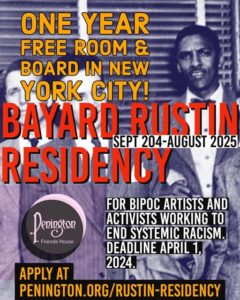

Penington Friends House is currently accepting applications for the 2024-2025 Bayard Rustin Residency. Deadline for submission is April 1st, 2024. Link to Application.

Penington Friends House is currently accepting applications for the 2024-2025 Bayard Rustin Residency. Deadline for submission is April 1st, 2024. Link to Application.

Building on the social activist history of Penington’s founders, original board, and later residents, the Bayard Rustin Residency at Penington Friends House (PFH) is envisioned as an ongoing ladder to empowerment for Black Indigenous and People of Color (BIPOC) working to end Systemic Racism and to create a culture of anti-Racism and intersectional equality in the United States of America. It is also intended to extend and strengthen the wider Quaker witness to equality.

Beginning in September of 2024, this residency will provide up to one year of room and board to a person who demonstrates a strong project that addresses ending Systemic Racism and who has a necessity to be in New York City for up to one year. They will reside at the Penington Friends House located in New York City’s Lower East Side of Manhattan. The Bayard Rustin Resident will demonstrate a need to live in Manhattan. Areas of focus of their work can include activism in the arts, policy change, human rights, community organizing, and other areas of activism focusing on ending racism and strengthening equality. Residents will meet regularly with the Residency Manager and will be expected to share their progress with the New York City community in the form of presentations or workshops.

For more information, please visit https://www.penington.org/rustin-residency/.

Students help clear 1700s Quaker cemetery at Tuttle’s Grove Methodist Church

Carteret County News-Times | Cheryl Burke

TUTTLE’S GROVE — The past and present met in a special way Sept. 19 when N.C. State University students spent the day cleaning up a Quaker cemetery, dating from the 1700s, nestled near a creek and wooded area behind Tuttle’s Grove Methodist Church on Highway 101.

The plot of land in front of the cemetery was given to the Quakers by Nicolas Briant in the 1700s as the site for a Quaker meeting house, according to Tuttle’s Grove church member and historian June Merrill.

Records show that the Core Sound Meeting House was built in 1736, and the Friends, another term used for Quakers, held their first meeting in the new structure Jan. 3, 1737. Tuttle’s Grove Methodist Church is located about 50 yards east of the original Quaker meeting house and contains some of the building’s lumber and beams.

“It is documented that on Sept. 23, 1737, Henry Stanton, a prominent leader in establishing the Quaker community in Carteret County, deeded two adjoining acres of pastureland to meet the need for a community cemetery,” Merrill said. “Benjamin Small was assigned to pale or fence in the graveyard.”

Merrill added that some of the fencing, including an old gate, remains on the site, where she estimates there are about 55 Quaker members buried. The graveyard is still used to this day and contains early county residents from the 1700s, 1800s and up to the present.

The cemetery had become overgrown with trees, underbrush and other debris.

The group of 10 students, who attend classes at the N.C. State University program in Havelock, agreed to donate time for their wellness day, which was Sept. 19, after members of Tuttle’s Grove contacted the program’s student director. The wellness day is set aside by the university for students to take a break for their mental well-being.

N.C. State sophomore Jared McCleery said he wanted to spend his time helping others.

“I wanted to come out and do something to help,” he said. “I think it’s really cool, and I’ve learned a lot.”

Junior Mack Harrison of Morehead City agreed.

“This is nice,” he said. “I’m a fan of history and preserving and restoring it.”

Merrill said the congregation appreciated the much-needed help.

“I think it is magnanimous of them to do this, and we are very thankful for their help,” she said.

The church hopes to refurbish the old cemetery so the public can enjoy it. Several old gravestones and bricks used to mark graves still lie broken or fallen over. In addition, old ballast stones from ships, used by Quakers to mark some graves, remain on the grounds. Merrill said other markers were “modest wooden headstones from cedar trees.”

Of the early Quaker leaders, one of the most legible headstones remaining today marks the grave of Joseph Borden, who died Jan. 6, 1825, at the age of 56.

“His marker is the only one in the ancient burying ground upon which the inscription can be raised (copied),” Merrill said.

The area’s Quaker population began to diminish in the early- to mid-1800s when division regarding the issue of slavery caused many in the church to leave the county and move to free states.

According to historical records and accounts by the late county historian F.C. Salisbury of Morehead City, a large group of Quakers, primarily from Rhode Island, came to what is now Carteret County as early as 1721 to establish homes and enjoy the freedom to worship. While historical records don’t say how Quakers traveled to the county, it is believed a great number of them came by boat, because two of the principal leaders of the group, William Borden and Stanton, were boatbuilders in Newport, Rhode Island. Little is known about Nicolas Briant who gave the land.

Borden settled in the Harlowe township, purchasing a large tract of land bordering the Newport River, where he established a sawmill and shipyard in the area known today as Mill Creek. Stanton took up his grant of 1,900 acres eastward from Core Creek. Merrill said many of the Quakers settled in communities along the Newport River, including Beaufort, Core Creek and Harlowe.

“They extended into adjoining counties, tending to follow rivers like the Trent and Pamlico,” Merrill said.

In the mid-1800s, Methodists were becoming increasingly active in the county, and the property was eventually transferred to The Methodist Episcopal Church South in Beaufort (Ann Street Methodist Church), according to Merrill. Half a century later, on Jan. 12, 1948, Ann Street Methodist Church deeded the property to the trustees of Tuttle’s Grove Methodist Church.

Merrill said when Tuttle’s Grove members voted in 2022 to split from the United Methodist Church, the building and property became an incorporated, independent Methodist Church with a board of directors. The property and building became theirs.

With that move came a renewed interest in fixing up the Quaker cemetery, making it attractive and accessible to those who want to see it. The church hopes to establish a level rock pathway, refurbish the grave markers and clear additional brush. They also hope to get it marked as a historical site. Church members are raising funds for the project.

As for what became of the county’s original Quaker population, Merrill said, “Quakers lingered in the area for more than 100 years after 1733. The coming of Methodists into Carteret County and the issue of slavery led to the decline in Quaker congregations. Pressure was brought to bear on the Friends for owning and hiring slaves to work their farmland. Also, younger ones among them associated with the Methodists and began ‘marrying out of unity.’ A sharp decline in their numbers seemed inevitable.”

A historical marker was placed in 1959 on Highway 101 in front of Tuttle’s Grove United Methodist Church to mark the original meeting house’s location.

“It was located slightly to the right of the present-day church and faced Beaufort,” Merrill said. “The building standing on the site today has in its framing all the lumber and beams its builders could reuse from the meeting house, which had stood in a state of disrepair for several decades. These early Methodists were being frugal and at the same time keeping the history of the Quaker church alive in the new structure.”

Construction of Tuttle’s Grove was started in 1902. The Rev. Daniel Herndon Tuttle, whose tent meeting on the site in 1898 started the church, returned to dedicate the new church.

Merrill said the cost of refurbishing the Quaker cemetery will be funded through donations from church members, friends and others interested in helping. Those interested can make checks payable to Tuttle’s Grove Methodist Church and mail them to the church treasurer, Lou Umstead, 2963 US Highway 70 E, Beaufort, NC 25816. Designate “Quaker Cemetery” on the memo line.

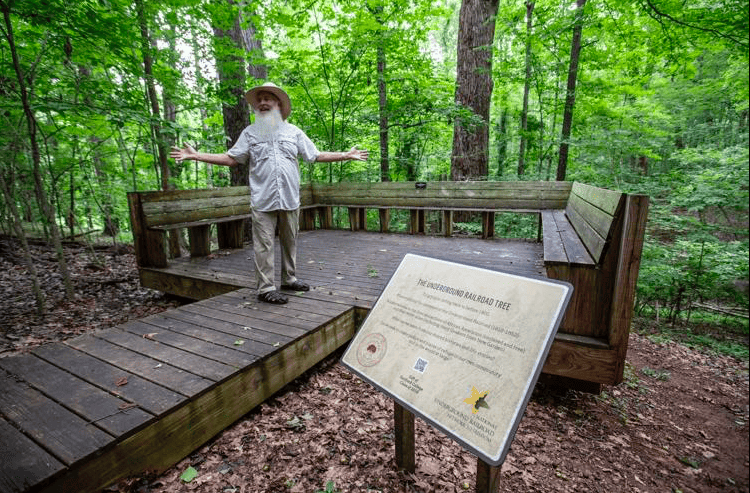

Nature’s call: Guilford’s Underground Railroad holds a history of heartache, hope

Greensboro News & Record | by Nancy McLaughlin

GREENSBORO — Determination and desperation.

Suffering and sadness.

Fear.

And hope.

They were all carried through this thicket of trees near Guilford College, which would later be known as the Underground Railroad.

“The footprints are long gone,” said local historian Max Carter of the New Garden Woods, which provided refuge on a path to freedom for an unknown number of slaves. “I’ve had people come here who are sensitive to these things who have stopped at the top of the hill because there is too much energy here.”

A tulip tree towering more than 140 feet and dating back to the 1800s has stood as a silent witness.

Still largely in its primitive condition, this piece of history sits insulated two blocks north of Friendly Avenue in one direction, and a quarter of a mile to Jefferson Road in another. Like Deep River in High Point and the Mendenhall Homeplace in Jamestown, Guilford County geography helps to tell the story of a time when the nation was divided by slavery.

The route through Greensboro that included the New Garden community has been called the Southern most successful Underground Railroad decades before the Civil War. Some white people who opposed slavery served as “conductors” along the route, helping those seeking freedom get from one “station” to the next.

The journey after here would have then taken about six weeks of walking to get slaves to a popular route through Indiana while traveling largely by night, not well clothed and foraging for food.

In those turbulent times, if you made it this far, to New Garden, was quite a feat. Freedom was within your grasp.

“This is where you ran to because of the Quaker community,” said Carter, the great, great grandson of conductors in Indiana.

****

The local portion of the Underground Railroad that extended through Guilford County ran though hundreds of acres of farmland once owned by Vestal and Alethea Coffin, believed to be the first conductors of North Carolina’s Underground Railroad. A Target retail store, a place of worship and Jefferson Elementary now sit on what had been more than 300 acres owned by the couple.

It’s where those Coffins met John Dimrey, a free Black man in 1819 who had been kidnapped and plotted with the couple to successfully escape his kidnappers.

The early Quakers in North Carolina were abolitionists who believed that any participation in slavery was inconsistent with Christian testimony. But those like the Coffins, who took part in hiding slaves, were later out of step with other Quakers who would not own slaves but saw it as the law of the land.

Once the Coffins and other sympathizers opened their doors, they were in trouble with the law.

The Guilford woods provided a measure of protection as slaves on the run made their way to a freedom they knew existed and wanted to experience.

As was the case of the slave woman given to her owner’s son, who had moved to Charlotte to start a family of his own. The woman tried to run so she wouldn’t be separated from her own family.

“This is where she would have hidden out,” said Carter, as a flicker of sunlight streams through the surrounding trees in the New Garden Woods, now known as the Guilford Woods. “They wouldn’t turn her away.”

But with a small baby in her arms, she later gave up.

Levi Coffin, Vestal and Althea’s younger cousin, went to her owner, David Caldwell, the noted preacher and politician, asking for mercy on her behalf. Caldwell was convinced to let her remain with her husband and children.

Those slaves who dared to escape did so with careful oral directions, sometimes passed through songs. The old Negro spiritual “Wade in the Water” was a reminder about routes and the best way for dogs to lose their scents.

Many were told at forks in the road to look for a tree with an embedded nail as a guide. Or never forget the secret greeting — three knocks followed by a pause and then two more — for food and shelter along the way.

“Conductors showed freedom seekers how to make a raft of four to six fence rails tied together with rope, cord or a vine,” according to the Guilford College archives. “After using this to cross the body of water, the slaves would cut apart the rails and float them downstream. Thus they would avoid leaving evidence of people having crossed.”

People have tread on significant portions of the Underground Railroad path through the New Garden community without knowing it. The Coffin property itself is now one of the busiest collections of roads in the area.

All around are echoes of a history that is unknown to some today, but is part of the county and country’s fabric.

Like Archibald and Vina Curry. They were free Blacks who had a 12-acre farm along Horse Pen Creek in between all the Coffin farms. After Archibald’s death, Vina went to work at the newly opened Quaker boarding school in the 1830s.

“While she’s scrubbing away, cooking and cleaning, she is interviewing young Black men because she still has her husband’s freedom papers,” related Carter, whose stories are often a part of the tours he gives along the local route of the Underground Railroad.

The freedom papers have no pictures, just a physical description of Archibald Curry.

Vina could’ve sold them. Instead, she found a novel way to use them to help others like herself.

“The integrity not to sell them but to give them to some Quaker like Levi Coffin, who would bring them back to her,” Carter said. “She got 15 men to freedom that way.”

****

Dr. George Howland Swain, a young Guilford County abolitionist in the early 1800s South, is buried in the New Garden Friends Meeting Cemetery. He helped a slave named Benjamin Benson successfully use the legal system for the first time in this country to gain his freedom.

Slaves, who were intentionally kept illiterate, couldn’t write their stories. So history mostly remembers them through the lives of those like the Coffins.

Swain, who died in 1852, was one of three members of the New Garden Quaker abolitionist community who took up the case of a free Black man who, in 1817, was kidnapped in Delaware and sold to Greensboro businessman John Thompson. After Swain, Vestal Coffin and Enoch Macy took up his case, Thompson sold Benson to a Georgia slave owner. Swain and the others later convinced a judge to order Benson back to Guilford County, where he later argued his own case in Superior Court — and won.

A historical marker stands outside the International Civil Rights Center & Museum downtown.

In the Guilford woods, though, history isn’t as obvious. Then as much as today, broken branches and overturned rocks are nondescript reminders of what once transpired.

Levi Coffin fed escaped slaves hiding in the woods near his grandparent’s farm, near where Western Guilford High now sits. He had found purpose in helping slaves after coming across a group of men, bound by chains, trudging down the road as a man on a horse with a whip followed closely. Then 7, he asked his father about what he saw and the elder Coffin explained slavery to him.

Coffin would eventually discover runaway slaves hiding in the New Garden woods while he was out doing chores.

Levi and his wife Catherine later joined Quakers moving to “free states” like Indiana where he turned their home into one of the most prominent stations on the Underground Railroad for slaves heading to Canada.

In subsequent years, Coffin wrote books sharing stories of the people on the Underground Railroad.

Said Carter: “It was much more difficult unless you were someone like Frederick Douglas, who taught himself to read, to tell that story. So a lot of what Guilford has been trying to do lately is to tell the story of people like Vina Curry and Arch Curry.”

But not all of that history can be found within the pages of a book.

Much of it is on dirt among the branches and bushes. In the New Garden woods. Where the footprints are long gone.