Greensboro News & Record | by Nancy McLaughlin

GREENSBORO — Determination and desperation.

Suffering and sadness.

Fear.

And hope.

They were all carried through this thicket of trees near Guilford College, which would later be known as the Underground Railroad.

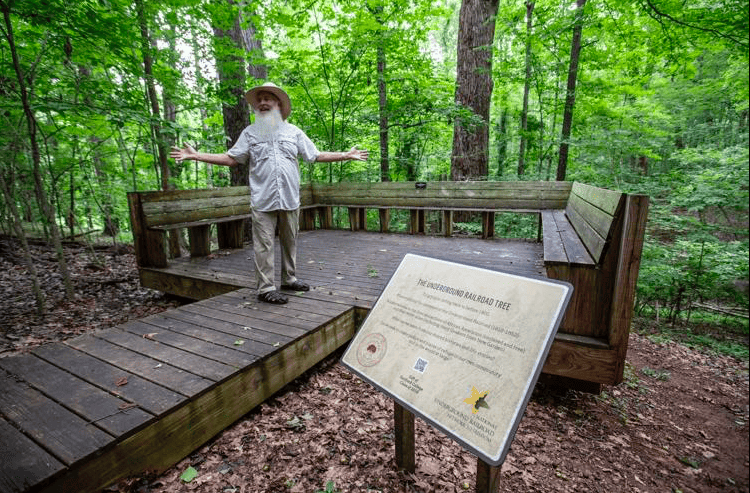

“The footprints are long gone,” said local historian Max Carter of the New Garden Woods, which provided refuge on a path to freedom for an unknown number of slaves. “I’ve had people come here who are sensitive to these things who have stopped at the top of the hill because there is too much energy here.”

A tulip tree towering more than 140 feet and dating back to the 1800s has stood as a silent witness.

Still largely in its primitive condition, this piece of history sits insulated two blocks north of Friendly Avenue in one direction, and a quarter of a mile to Jefferson Road in another. Like Deep River in High Point and the Mendenhall Homeplace in Jamestown, Guilford County geography helps to tell the story of a time when the nation was divided by slavery.

The route through Greensboro that included the New Garden community has been called the Southern most successful Underground Railroad decades before the Civil War. Some white people who opposed slavery served as “conductors” along the route, helping those seeking freedom get from one “station” to the next.

The journey after here would have then taken about six weeks of walking to get slaves to a popular route through Indiana while traveling largely by night, not well clothed and foraging for food.

In those turbulent times, if you made it this far, to New Garden, was quite a feat. Freedom was within your grasp.

“This is where you ran to because of the Quaker community,” said Carter, the great, great grandson of conductors in Indiana.

****

The local portion of the Underground Railroad that extended through Guilford County ran though hundreds of acres of farmland once owned by Vestal and Alethea Coffin, believed to be the first conductors of North Carolina’s Underground Railroad. A Target retail store, a place of worship and Jefferson Elementary now sit on what had been more than 300 acres owned by the couple.

It’s where those Coffins met John Dimrey, a free Black man in 1819 who had been kidnapped and plotted with the couple to successfully escape his kidnappers.

The early Quakers in North Carolina were abolitionists who believed that any participation in slavery was inconsistent with Christian testimony. But those like the Coffins, who took part in hiding slaves, were later out of step with other Quakers who would not own slaves but saw it as the law of the land.

Once the Coffins and other sympathizers opened their doors, they were in trouble with the law.

The Guilford woods provided a measure of protection as slaves on the run made their way to a freedom they knew existed and wanted to experience.

As was the case of the slave woman given to her owner’s son, who had moved to Charlotte to start a family of his own. The woman tried to run so she wouldn’t be separated from her own family.

“This is where she would have hidden out,” said Carter, as a flicker of sunlight streams through the surrounding trees in the New Garden Woods, now known as the Guilford Woods. “They wouldn’t turn her away.”

But with a small baby in her arms, she later gave up.

Levi Coffin, Vestal and Althea’s younger cousin, went to her owner, David Caldwell, the noted preacher and politician, asking for mercy on her behalf. Caldwell was convinced to let her remain with her husband and children.

Those slaves who dared to escape did so with careful oral directions, sometimes passed through songs. The old Negro spiritual “Wade in the Water” was a reminder about routes and the best way for dogs to lose their scents.

Many were told at forks in the road to look for a tree with an embedded nail as a guide. Or never forget the secret greeting — three knocks followed by a pause and then two more — for food and shelter along the way.

“Conductors showed freedom seekers how to make a raft of four to six fence rails tied together with rope, cord or a vine,” according to the Guilford College archives. “After using this to cross the body of water, the slaves would cut apart the rails and float them downstream. Thus they would avoid leaving evidence of people having crossed.”

People have tread on significant portions of the Underground Railroad path through the New Garden community without knowing it. The Coffin property itself is now one of the busiest collections of roads in the area.

All around are echoes of a history that is unknown to some today, but is part of the county and country’s fabric.

Like Archibald and Vina Curry. They were free Blacks who had a 12-acre farm along Horse Pen Creek in between all the Coffin farms. After Archibald’s death, Vina went to work at the newly opened Quaker boarding school in the 1830s.

“While she’s scrubbing away, cooking and cleaning, she is interviewing young Black men because she still has her husband’s freedom papers,” related Carter, whose stories are often a part of the tours he gives along the local route of the Underground Railroad.

The freedom papers have no pictures, just a physical description of Archibald Curry.

Vina could’ve sold them. Instead, she found a novel way to use them to help others like herself.

“The integrity not to sell them but to give them to some Quaker like Levi Coffin, who would bring them back to her,” Carter said. “She got 15 men to freedom that way.”

****

Dr. George Howland Swain, a young Guilford County abolitionist in the early 1800s South, is buried in the New Garden Friends Meeting Cemetery. He helped a slave named Benjamin Benson successfully use the legal system for the first time in this country to gain his freedom.

Slaves, who were intentionally kept illiterate, couldn’t write their stories. So history mostly remembers them through the lives of those like the Coffins.

Swain, who died in 1852, was one of three members of the New Garden Quaker abolitionist community who took up the case of a free Black man who, in 1817, was kidnapped in Delaware and sold to Greensboro businessman John Thompson. After Swain, Vestal Coffin and Enoch Macy took up his case, Thompson sold Benson to a Georgia slave owner. Swain and the others later convinced a judge to order Benson back to Guilford County, where he later argued his own case in Superior Court — and won.

A historical marker stands outside the International Civil Rights Center & Museum downtown.

In the Guilford woods, though, history isn’t as obvious. Then as much as today, broken branches and overturned rocks are nondescript reminders of what once transpired.

Levi Coffin fed escaped slaves hiding in the woods near his grandparent’s farm, near where Western Guilford High now sits. He had found purpose in helping slaves after coming across a group of men, bound by chains, trudging down the road as a man on a horse with a whip followed closely. Then 7, he asked his father about what he saw and the elder Coffin explained slavery to him.

Coffin would eventually discover runaway slaves hiding in the New Garden woods while he was out doing chores.

Levi and his wife Catherine later joined Quakers moving to “free states” like Indiana where he turned their home into one of the most prominent stations on the Underground Railroad for slaves heading to Canada.

In subsequent years, Coffin wrote books sharing stories of the people on the Underground Railroad.

Said Carter: “It was much more difficult unless you were someone like Frederick Douglas, who taught himself to read, to tell that story. So a lot of what Guilford has been trying to do lately is to tell the story of people like Vina Curry and Arch Curry.”

But not all of that history can be found within the pages of a book.

Much of it is on dirt among the branches and bushes. In the New Garden woods. Where the footprints are long gone.